Intro

Like I said in the previous part Bloodhound I - Ranking Web Resources, at some point I stumbled upon this article from James Kettle about Backslash Powered Scanning.

Backslash Powered Scanning

Commercially available vulnerability scanners often don’t perform as well as we would like them to. The most basic implementation you can find is a simple word list with known payloads that you can iteratively test against an application.

James Kettle’s own words:

“…web application scanners are widely regarded as only being fit for identifying ‘low-hanging fruit’ - vulnerabilities that are obvious and easily found by just about anyone. This is often a fair judgement; in comparison with manual testers, automated scanners’ reliance on canned technology-specific payloads and innate lack of adaptability means even the most advanced scanners can fail to identify vulnerabilities obvious to a human.”

He then created the concept of Backslash Powered Scanning with the goal of “automate human intuition”. The method works similarly to how a human would manually test an application for vulnerabilities. It looks for behavior changes when you give problematic character sequences as input, and modify future payloads based on these findings.

In practice

A manual testing workflow can be broken down into a couple of simple questions:

- How does the page behave when I give it the expected input?

- How does it behave when I give it unexpected input?

- Does it elicit an error?

- …

Simple Example

Take a very common product search page /products?search=<filter> as an example:

- When sending an empty input

/products?search=- The page responds with status code

200 - The page responds with every product it has stored in its database

- The page responds with status code

- When sending a valid input

/products?search=cake- The page responds with status code

200 - The page responds with only cake products

- The page responds with status code

- When sending a valid input

/products?search=spaceship- The page responds with status code

404 - The page responds with a “not found” message

- The page responds with status code

After executing these requests, even without a basic understanding of how HTTP status codes work, some behavior can be inferred:

- The page responds with status code

200when a product is found - The page responds with status code

404when a product is not found - The content-length varies for every request, but seems to stay the same for the same input.

- The page always responds with

text/htmlcontent

So how does the page behave when I send special characters?

- When sending an invalid input

/products?search=cake'- The page responds with status code

500 - The page responds with content type

application/json - The page content is an error message.

- The page responds with status code

This shows that the added special character makes the page behave differently.

SSTI on known template

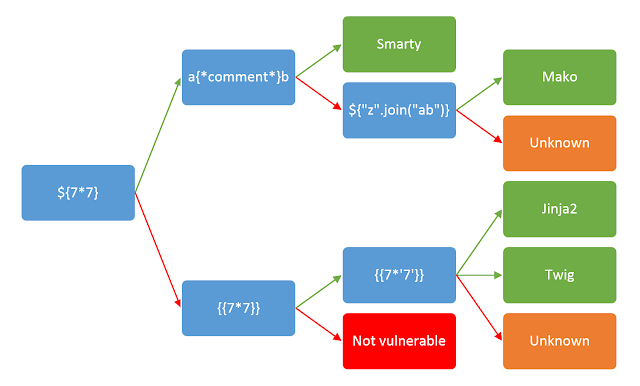

One of the steps of exploiting a Template Injection vulnerability is identifying which template engine is being used. The following diagram outlines the process of identification:

The diagram was taken from this PortSwigger post

Using the previous example, you would start by sending a generic payload containing a series of special characters:

- GET

/products?search=${{<%[%'"}}%\.- The page responds with status code

500 - This shows that the user input is used in a context where one of those characters has a syntactical role, and might be vulnerable to template injection.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=${7*7}- The page responds with status code

200 - The template does not render the formula, printing it as text.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search={{7*7}}- The page responds with status code

200 - The template renders it as “49”.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search={{7*'7'}}- The page responds with status code

200 - The template renders it as “49”, meaning that the template engine being used is

Twig.

- The page responds with status code

This process is definitely already automated in tools like SSTImap, the difference here is how the recognition of the template engine is integrated inside the scanner itself, removing the need to run these tools externally.

SSTI on unknown template

In my opinion, the biggest highlight is the ability to identify the behavior, even if complete template identification is not possible.

- GET

/products?search=${{<%[%'"}}%\.- The page responds with status code

500

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=${7*7}- The page responds with status code

200 - The template renders it as “49”.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=a{*comment*}b- The page responds with status code

200 - The template renders the payload as is.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=${"z".join("ab")}- The page responds with status code

200 - The template renders the payload as is, meaning it is not possible to identify the template engine.

- The page responds with status code

Because the scan works in an iterative mode, even if it was unable to identify the template, it can still know that there is a template engine processing that accepts a numeric context. This kind of information enables us to continually investigate and exploit, even on technologies that are not widely known.

Processing response content

A big part of understanding the page’s behavior is how to interpret the response body, identifying what is expected to change for every request and what is expected not to change. Think of a landing page of a product company, where every time the page loads it shows a review of a different customer on the header. The content length of this page will always change, no matter the input you give it.

There are some attributes that can be used to classify the behavior of a page:

- Status Code

- Header Count

- New Line Count

- Space Count

- Informed and the inferred content type

- Structure Hash

- Is the input reflected? How many times?

- Are there any known patterns present?

- This is evaluated as a count of each occurrence, where if the number changes, it can signal a stack trace or internal information being leaked.

These attributes should be mostly stable between valid requests, and we can identify how they change by making multiple valid requests between the malicious requests.

The following malicious payloads were lifted directly from the original open source implementation: Backslash Powered Scanner

- GET

/products?search=milk`z'z"${{%{{\- The page responds with status code

500 - Content type is

application/json - The payload can’t be found on the page.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=milk- The page responds with status code

200 - Content type is

text/html - The word “milk” is found once on the page.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=milk\z`z'z"${{%{{\- The page responds with status code

500 - Content type is

application/json - The payload can’t be found on the page.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=milk- The page responds with status code

200 - Content type is

text/html - The word “milk” is found once on the page.

- The page responds with status code

- GET

/products?search=spaceship- The page responds with status code

200 - Content type is

text/html - The payload can’t be found on the page.

- The page responds with status code

Looking at the results, we can see that when sending malicious requests, the page will always answer with status code 500 and content type application/json, meaning that in a malicious context these attributes are invariant. Similarly, when sending valid requests, the page will always answer with status code 200 and content type text/html, but it is not guaranteed that the payload will be found on the page, meaning that the payload reflection is a variant attribute (in this context, the payload was not reflected because the product “spaceship” was not available).

This means that:

- When sending malicious payloads, the status code and content-type will always be the same.

- When sending valid inputs, the status code and content-type will always be the same, but the input will not always be reflected.

This allows us to understand how the page behaves when presented with a future malicious payload, making it possible to easily tell if the page is or is not vulnerable to a certain kind of attack.

Structure Hash

The page can dynamically change the content that is being shown, showing different text or changing what image is being shown based on different conditions. But this is all done inside the same pre-existing HTML structure (most of the time, at least).

Think of the following template as an example:

...

<div class="content">

<p>Hello <div class="name-colorful">{{ user.name }}</div>! Good Morning.</p>

</div>

...

The name that will be shown can change, and it will make the final content length vary for every user, but the existing structure around the name will always be the same.

So if you create a hash of that structure div > p > div > /div > /p > /div, this will always be the same, regardless of the user that is requesting the page.

Informed x inferred Content-Type

The content type can be defined as whatever the server wants it to be, which is not always necessarily true. For example, someone might manually set their content type header to always return text/html, but if an internal server error occurs, the framework might return a JSON object. Because of that, it is essential to not only rely on whatever the server is telling you, but to check it yourself as well.

Presence of known patterns

Another metric that is important to consider is if there was a change in the amount of occurrences of known patterns. These patterns might be words that are used to identify leakage of information by the server.

This can be achieved by doing a single count for words that you would definitely find in a stack trace or error message, for example: error, exception, true, false, among others. Most of the time, the page as intended will never include these words, and this count will most likely differ when comparing against the response of a malicious payload.

Outro

All the techniques mentioned above, in combination with carefully crafted payloads, can be used to identify and iterate over the page behavior, enabling automated detection, or at least the signaling, of vulnerabilities.

This technique is by no means my own, and my implementation is all derived from the original open source project that can be found here.